Holidays are a celebration of an event or practice so integral to all cultures, bringing language, food, and more. When taking a look at the American holiday, a common theme arises; the distancing from the old cultural roots into the morphing of these holidays, as an excuse to get people out of their houses and spending money. As February approaches, so do more of these holidays, and there is no better display of consumeristic holidays than Valentine’s Day. To understand the effects American consumer culture and capitalism have on holidays like Valentine’s Day, we must first familiarize ourselves with the origins of the holiday.

In the case of Valentine’s Day, the holiday originated as a celebration of martyrdom. Martyrdom is the act of killing someone due to their religious beliefs, which was a practice often done in the Roman Empire, which is where Valentine’s Day holds its origin. While many of these people were named, “Valentine,” the two that are the namesake of Valentine’s Day are Valentine of Rome and Valentine of Temi. The former was martyred in the year 269, and the latter in the year 273. Both Valentine’s were important to the Christian religion (with Valentine of Rome being a priest, and Valentine of Temi being a bishop), and as such, the Western Church of Christendom at the time declared February 14 as “The Feast of Saint Valentine” in honor of the two saints.

However, this new Christian holiday fell between the Roman holiday of Lupercalia and Juno Februa. Both of these pagan holidays (which fell between February 13 and 15) were in honor of the gods Pan and Juno, who were the gods of love, marriage, and fertility. Despite this, Valentine’s Day at the time did not have any connections to love, not until a poem that Geoffrey Chaucer wrote on the day linked the two. The poem was written at least seven hundred years after the first known celebration of Valentine’s Day. Furthermore, the first known depiction of Valentine’s Day as an annual celebration of romance was not until the year 1400 in the Charter of the Court of Love, written by Charles VI of France. This charter depicted Valentine’s Day as a lavish celebration filled with food, song, dance, poetry, and jousting.

The commercialization of Valentine’s Day in America can be traced back to the mid-1800’s. During this era, the celebration of Valentine’s Day had made its way to England, where it was celebrated by giving fancy Valentine’s Day cards with ribbons and intricate depictions of hearts, flowers, and Cupid. In England, these cards were popular enough to be mass produced in factories, and in 1847, Esther Howland, an entrepreneur from Massachusetts, decided to mass produce these types of cards in America. These celebrations in America and England began the long tradition of companies creating stuff for people to buy on Valentine’s Day. Along with these cards, in 1868, the English chocolate company Cadbury created the first heart-shaped chocolate boxes for Valentine’s Day.

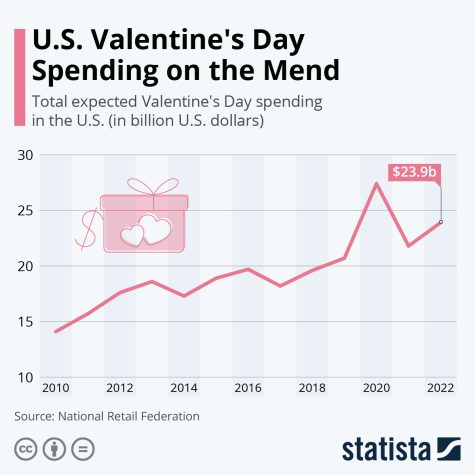

The commercialization of Valentine’s Day follows the much broader trend of American corporate erasure of holiday meanings and culture from most of the holidays the Western world celebrates today. Americans alone spent $23.9 billion on Valentine’s Day related items in 2022, which is larger than the GDP of sixty-nine countries. This would all be fine (or at least less detrimental), of course, if this commercialization did not also have effects on those who are single and those in relationships. For those in relationships, the pressure is on, especially for males, to spend money on their significant other during Valentine’s Day. According to a British study, one in ten men will spend £75 on their significant other during Valentine’s Day, while one in three women will spend less than £10 on their significant other. The commercialization of Valentine’s Day further reinforces outdated gender norms, which are detrimental for both men and women.

The commercialization of Valentine’s Day also leads to mental health issues for those with alternative methods of showing love, as well as simply the general populace. In the same British study, fifteen percent of women in the U.S. buy themselves flowers on Valentine’s Day; a sign of feeling left out from those in relationships. Furthermore, a study conducted by the University of Michigan concluded that people with “avoidant attachment” styles, as in, those who dislike intimacy and are less likely to provide emotional support, are more likely to have lower levels of satisfaction and investment into the holiday. Lastly, for those who have experienced traumatic moments in regard to relationships, the constant marketing and advertising on Valentine’s Day can be dreadful for these people.

It is clear that the over-commercialization of Valentine’s Day is yet another way for companies to make a quick buck at the expense of the general populace and its culture. While Valentine’s Day is not unique in commercialization (for example, Christmas being originally made to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ, now being a holiday about getting gifts and a mythical man in a red suit which, in its modern state, was created by Coca-Cola to sell more soda), it is unique in the effects outside of just the clear cut effects capitalism has on culture. The commentary of the commercialization of Valentine’s Day by many people should not be taken as a statement against the holiday, but rather a sign to reclaim holidays and “de-commercialize” them, by being more open minded about capitalisms’ goals when it comes to selling the populace products, distracting consumers from the real goal of holidays—celebration and joy.