South Slav Sentiments 2: Fall of the Union of Southern Slavs

In 1980 Josip Broz Tito, communist dictator of Yugoslavia, died. In the following two decades, his life’s work of preserving a hotbed of different ethnic and religious groups under one country fell apart. This was not the intended outcome of the founders of Yugoslavia, wanting to unite the Southern Slavic peoples under one flag against the oppression of the Austrians and Ottomans. The founders wanted the Slavic tribes which migrated to the Balkans in the 600s to unite under the leadership of the Serbs. However, their ideal Kingdom of the South Slavs (Yugo=South) was, unfortunately for the Serbs, not going to work out. The Old Serbian Empire did not even encompass all of the lands given to the Serbs after WWI. To understand the motivation for creating a Southern Slav kingdom, and why it ended up failing, requires the understanding of how a people changed over the course of 1,400 years.

When the Southern Slavs migrated to the Balkans, they brought along their Slavic religion. That would change as it was politically advantageous to convert to Christianity, as their neighbors were Christian and their Northern brethren had experienced what happens when one does not convert to Christianity; a dubious claim to their land will be forged to justify a forceful and bloody conversion of the entire populace. Since the Southern Slavs were Christianized, it should mean that they had an even stronger bond than culture and language alone. Except there were other powers at play for their disunity: the rivalry between the Church of Rome and the Church of Constantinople. In 754, after Rome had been isolated from Eastern Roman control, the Patriarch of Rome (the Pope) used Frankish help to formally declare independence from Eastern Roman control. While the Christian Church would remain officially united for centuries, divisions had formed before the independence of the Pope and had started to accelerate. The consequences of this would have drastic consequences on the Christian world, especially on the Southern Slavs, on which “rite” of Christianity to practice.

The Balkans from the 700s to 900s were in a state of limbo over which rite would dominate. The Slavs were nomadic, western Christians did not expand into the Balkans yet and the Eastern Roman Empire had lost its dominance of the Balkans, leaving no inherent dominating force besides the Bulgarians. The Bulgarians followed the Rite of Constantinople, but they were in constant conflict with the Eastern Roman Empire and threatened several times to receive their crown directly from the Pope. Still, the Bulgarians only dominated the Eastern Balkans, the Western Balkan Slavs had to make a choice, and their choice was influenced by geography. The Croatians and Slovenes were in the Northwest of the Balkans. To their west and north were followers of the Rite of Rome. To the South, the Serbs had the followers of the Rite of Constantinople to the East and South. Then there was Bosnia. Though not yet a separate identity, Bosnia was in the middle of both. The decision of which rite to follow was a hard one to chose. This is why the rulers of Bosnia changed allegiance based on the dominating power of the Balkans, leading the “Bosnians” to switch from each rite dozens of times.

To make matters worse, in 1054 after disagreements over practices like the type of bread, the two rites formally split into two churches: The Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Now accusing the other of being heretics, the choice of which church to follow became more dire. At this point the Eastern Roman Empire reasserted its dominance over the Balkans, and for a time being, ruled over the Southern Slavs. They lost control over Croatia and Bosnia, but Serbia remained under their rule until 1180. Still Serbia would remain Eastern Orthodox up until this day. By the same token, right to the north the Hungarians settled and established a kingdom following the Catholic Church and subjugated the Croatians as a vassal state of Hungary, ensuring the Croatians would remain Catholic up to this day. The Slovenians were incorporated to the Catholic Holy Roman Empire. Still no dominating force would remain in effect in Bosnia, meaning neither sect had an established church and proper organization in that region. Catholicism became part of the Slovenian and Croatian identity and Eastern Orthodox part of Serbian identity. The religion of the “Bosnians” was that which was advantageous, by their rulers at that time. Priests, bishops, the general clergy, and church structures were severely lacking in Bosnia from either church. This lack of a strong religious institution in Bosnia would be why when a strong religious institution came. Islam found a surprising amount of converts, which when looked at closely isn’t surprising.

In 1354, the Muslim Ottoman Turks established a firm foothold into the Balkans, which would be used to conquer the rest of the Balkans. Constantinople fell in 1453, and the Serbs and Bosnians by 1540. Under Ottoman rule, Christians were treated as second class citizens and some found it advantageous to convert to Islam to no longer be second class citizens. This was especially apparent in central Bosnia, where most of the Slavic Muslims would come to live. Without established Christian institutions and traditions, and with the advantages of converting, it was even easier to convert the Slavs in Bosnia. This set the stage for the disunity which made Yugoslavia collapse in 1991. These 3 different religions would not show the true extent of their differences, which existed until after Yugoslavia formed in 1918.

Serbia gained autonomy from the Ottoman Empire in 1815 after a series of disastrous wars which weakened the empire. The Serbs continued to eye lands with South Slavic majorities in the Austrian and Ottoman Empire. The Balkan Wars almost fully kicked the Turks out of the Balkans. The next target was Austria, which occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina after the Crimean War; when Russia tried to increase its influence on the Christian minorities of the Ottoman Empire. This would lead to resentment among Serbian nationalists against Austria and would lead the world to war. The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria by Gavrilo Princip, a self proclaimed Yugoslav, justified an Austrian declaration of war on Serbia in 1914, and through a series of alliances led to the start of WWI. The war would establish Yugoslavia at the cost of millions of lives. Yugoslavia wasn’t officially called Yugoslavia until 1929 as it was the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, the Kingdom of Serbia and Montenegro. When it was officially called Yugoslavia, Slovene, Croatian and Bosniak (Muslim South Slavs) critics would refer to it as “Greater Serbia”. The state was established by the Serbs, and was from the onset Serb dominated. The capital was the Serbian capital of Belgrade and the ruling class was Serbian. Nationalistic expressions were banned and heavily suppressed in non-Serb regions. Underground nationalist groups formed wanting independence, the most prominent was the fascist Croatian revolutionary group Ustaše who helped assassinate Alexander I. His son Peter II was too young to lead the nation and the nation was ruled by a regency council, which gave into Croatian demands of autonomy which bordered on independence. Then in 1941, with the Axis claiming Italian, German and Hungarian minorities oppressed in Yugoslavia, invaded and occupied the nation in 12 days.

Slovenia was occupied by Germany, Italy and Hungary. Croatia was set up as an independent puppet state with the Ustaše collaborating. The Catholic Church of Croatia gave its blessing to this act and the Ustaše helped in occupying the rest of Yugoslavia. The Ustaše helped in the Holocaust, but also took their own liberties in cleansing non-Croatians from the new puppet state, specifically the Bosniaks and Serbians. This is not to say that Croatians as a whole turned as genocidal Nazis, many Croatians were part of Tito’s communist resistance force. Tito himself was half Croatian and half Slovenian. There were on the Serbian side the Chetniks; who were pro-monarchy Serbian nationalist partisans who had their fair share of violence against Croatians and Bosniaks. In the end, Tito’s pan-Yugoslav resistance force liberated Yugoslavia from Nazi rule, and Tito became its dictator in 1945.

Tito’s agenda was to quell nationalistic and religious tensions in Communist Yugoslavia, though not to the same extent as Alexander I, who inspired Croatian independence. The crimes of the Ustaše and Chetniks were to be punished. The differing nationalities: the Serbs, Slovenes, Croatians, Bulgarians/Macedonians, Albanians and Bosniaks, would have the same rights. The Serbs, Slovenes, Croatians, Bulgarians/Macedonians and Bosniaks would have their own republic, Albanians an autonomous area in Kosovo in the Republic of Serbia. National flags would be allowed to display if they had the communist red star on it. Local languages would be allowed and not suppressed. No more Serbian dominated Yugoslavia. Separatist nationalism was to be duly suppressed. From 1945-70 Yugoslavia enjoyed relative stability and growth. Then in 1970 OPEC hiked up oil price against the US and European countries, including Yugoslavia. This started a chain reaction which led to economic collapse of Yugoslavia. Prices were on the rise and the government borrowed too much money from the West to finance development. Growth dropped, and so did employment and income. So began the standard human weakness: when crisis comes, use scapegoats to absolve oneself of blame.

The economic crisis was used by nationalist to blame other nationalities of ruining the country. Such talk was only temporarily suppressed. In 1974, representatives of the Republic of Croatia accused Serbia of dominating Yugoslavia and pushing Serbian agendas on the other republics, and demanded a weakening of Serbian power in Yugoslavia. Tito responded by passing the Constitution of 1974 which not only weakened Serbian power by allowing its two autonomous provinces (Vojvodina and Kosovo) to vote on national affairs, but also allowed for republics to secede unless blocked by the other republics. While this appeased the Croatians, the Serbs felt as their rights were being limited in exchange for growing Croatian power. Then, in Kosovo, ethnic tensions between the Serbs and Albanians erupted in 1987. Slobodan Milošević, a high ranking Yugoslav communist, while claiming the usual anti-nationalist lines of Tito, did support the Serbian minorities in Kosovo and claimed that they were being oppressed by the Albanian dominated government. This justification of ethnic distrust by the Serbian nationalists by a high ranking government official fanned the flames of separatism. The Serbs had an attachment to the province, it was the sight of their heroic defeat against the advancing Muslim Ottoman Turks in 1389, though by 1980 they were in the minority. The Muslim Albanian majority was perceived as similar to the Turkish invaders 600 years earlier, violent and oppressive. Indeed, most distrust of the Muslims, whether they were Bosniak or Albanian, was compared to the centuries old struggle of the Serbs against their Muslim Turk oppressors.

Slobodan Milošević portrayed the attempts of Ivan Stambolić, the president of Yugoslavia, to suppress Serbian nationalism as suppression of the Serbs themselves. Under increased accusations, Stambolić resigned in disgrace. Milošević became an increasingly powerful figure, and increasingly became less subtle in his Serbian nationalism. He called for Serbian majority provinces in Croatia and Bosnia to being annexed into the Serbian republic. Such blatant calls for the strengthening of Serbian authority worried Croatia, Slovenia and Macedonia, and the Crusade-like references that instill nationalistic fervor understandably worried the muslim Bosniaks and Albanians. Milošević installed loyal figureheads using popular revolutions by Serbs in Montenegro, Vojvodina, Kosovo and Serbia. He effectively controlled half of Yugoslavia by 1989. Milošević demanded emergency powers in Kosovo when the Albanians went on strike in order to have their Albanian leader reinstalled, the president of Yugoslavia Raif Dizdarević, a Bosniak, denied his requests. Milošević is quoted as saying, “I don’t care if it’s not constitutional.” When heard by the Slovenian Communist leader Milan Kučan, he went home and gave a speech supporting the protesters in Kosovo saying that they are protesting for their rights and the rights of every republic in Yugoslavia. This was broadcasted in Serbia as well, with a voiceover accusing Milan Kučan of advocating for Slovenian and Albanian separatism. This led to a popular Serb march onto the federal parliament building calling for Milošević to be granted the emergency powers. Milošević demanded that Dizdarević face the crowd, and when Dizdarević said he feared that he would be “thrown into the river,” Milošević responded by saying, “we cannot control what happens if you do not give us the powers we demand.” Dizdarević faced the crowd and spoke about brotherhood and unity, to be met with boos and jeers. Milošević had effectively appealed to emotions of the Serbian people to ignore unity of the Yugoslavia for the unity of the Serbs under a “Greater Serbian Republic.” This spectacle was broadcast and was seen in every republic, and at this point the eventual fall of Yugoslavia was inevitable. Milošević was granted emergency powers and used the military to enforce his will on Kosovo, crushing protests and arresting popular leaders. The military was now seen by the other republics to create Greater Serbia.

The first republic to take action against Serbia was Slovenia. In Slovenia, Kučan allowed a free press which actively criticized Milošević. Popular magazines in Slovenia such as Mladina portrayed Milošević as a Nazi and an incompetent crusader. Milošević and his loyalists demanded Kučan to take action and suppress the press. Kučan took no action. Then a leaked document from a meeting between Milošević, and high ranking Serbian security officials, made out the magazine Mladina to be funded by the CIA and to be counter-revolutionary. Counter-revolutionary was the same charge that was thrown against the Kosovo protesters. The document was released and Belgrade demanded Kučan arrest the staff. A key member of Mladina was arrested, but this only helped fuel separatist sentiments. Kučan essentially cooperated with Mladina after this arrest, and changed the Slovene constitution to keep Belgrade out of Slovenian affairs. In response, Milošević organized Serbian nationalists to hold a demonstration in the Slovene capital, Ljubljana, and make Kučan out as a traitor. However, Milošević faced opposition from Slovenia’s friend: Croatia, which barred access of the demonstrators from moving into Slovenia from Croatia. Milošević in response called a congress with representatives from every republic.

The Slovenian delegation at the congress made demands to insure their sovereignty and lessen the dominance of Serbia. By this point the amount of control Milošević had over Yugoslavia was apparent, and he had all the demands voted down. The Serbs cheered each time, and it infuriated the Slovenian delegation. The Slovenians in response walked out and seceded from the Yugoslavian Communist Party. The first republic was on its way to leaving. Immediately after, the Croatian delegation walked out in unity with the Slovenes. A peaceful solution to keep Yugoslavia together seemed less and less possible. Then, in 1990, free elections were held in all of the republics, and Milošević was elected president in Serbia and nationalist Franjo Tuđman was elected in Croatia. Franjo Tuđman kissed the Croatian checkerboard flag, which was the same flag used by the fascist Ustaše. This worried the Serbian minorities in Croatia, especially in the southern town of Knin where the police and population were majority Serbian, where the police refused to accept the Croatian government which waves the checkerboard flag. Indeed, Tuđman’s rhetoric of establishing a strong Croatia was later admitted by his staff to have been a poor choice of words which pushed away the Serbs who wished to live peacefully in Croatia, essentially forcing them to ally with Serbian nationalists. When Croatian representatives went to Knin to calm the situation with the police, the police started jeering the representatives. This would lead the representatives to be afraid of their lives even willing to: “Promise them a Serb state- anything to get us out of here.” The Serb mayor of Knin met with Milošević and the staff which controlled the Yugoslav army. Members of the staff advised the town to fortify itself to protect against the Croatian fascists, which had 45 years ago committed widespread genocide against the Serbs in Croatia.

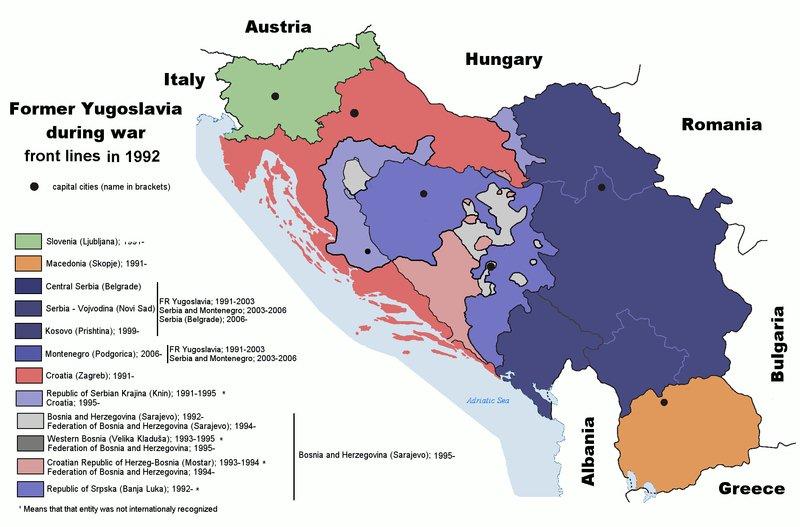

Knin was at a vital roadway and railway intersection in Croatia, and the Yugoslav military would do nothing to stop the Serbs in Croatia. Realizing they needed to arm their own military, Croatians appealed for arms from foreign powers. They went to the US but were rejected, but made a deal with recently independent Hungary to smuggle arms and munitions into Croatia. News of this reached Belgrade which demanded Croatia give up its illegally purchased arms. To help leverage Tuđman, a leaked film was broadcasted that had high ranking Croatian officials meet with smugglers to conduct terrorist attacks against the Serbs in Croatia. Despite this, the Croatian people rallied behind Tuđman who refused Belgrade’s demands. Next Milošević attempted to let the Supreme Council to allow him to use the Yugoslav military to disarm Croatia in 1991. They needed 5 out of the 8 votes to allow military force to be used. Slovenia did not show up. Macedonia and Croatia voted no. Serbia, Vojvodina, Kosovo, and Montenegro voted yes. Then came Bosnia’s turn to vote, and while the representative was of Serbian ethnicity, he surprised the whole council by voting no. This made the Serbs angry at the Bosnians who were seemingly collaborating with the Croatians. Slovenia and Croatia declared independence in the summer of 1991 by expecting that the Serbs were unable to stop them.

Besides a showdown between Yugoslav border guards and the Slovene militia, Slovenia was allowed to leave Yugoslavia as it had no major Serbian minority. Croatia on the other hand was a different story. It contained about 600,000 Serbians, some of whom occupied towns with large Serbian minorities and aimed with seceding from Croatia to rejoin Yugoslavia. Tuđman, who was now the president of an independent Croatia, and the extreme nationalists of the government ordered attacks on these Serbian separatist towns to incite a reaction from the separatist Serbs. This was to justify the expulsion of these Serbian minorities to have a strong ethnically pure Croatia. Further attempts to drive out these Serbian strongholds were meant with failure and loss of Croatian life. This was used as propaganda to incite further Croatian resentments against Serbia, widespread burning Yugoslav flags occurred. Only a month after Croatia declared independence, Serbia invaded in order to protect Serbian minorities. In order to bolster the Yugoslav army, Belgrade armed and uniformed thousands of criminal gangs and nationalistic fanatics, such as the formerly suppressed Chetniks. The volunteers after capturing village after village, committed widespread atrocities against the Croatian locals such as hacking them to death with axes or burning them alive. Their bodies were strung up on display as a warning. The War for Croatian independence became a war for the survival of the Croatian people, and on the Serb side, a war to protect the oppressed Serb minorities. Increasingly, Croatian populations were expelled and fled westward towards the capital, and the Serbs expelled fled east towards the Yugoslav army. The European Committee tried intervening, and had Milošević agree to a cease fire if the human rights of the Serbs in Croatia were to be protected. Milošević however proved his word was not to be trusted as he rescinded his acceptance and accused the EC of attempting to dismantle Yugoslavia. Indeed, it could be reasonably argued that they were, as the provisions drawn would allow the other republics which still remained to leave Yugoslavia. Despite Milošević’s objection, Macedonia and Bosnia seceded.

While the war was going well in Croatia and UN troops were sent to protect Serbian gains, the crisis in Bosnia took the genocide to a new level. Bosnia was about 30% Serbian, 40% Bosniak and 20% Croatian. The Croatian and Bosniaks formed a large enough coalition to leave Yugoslavia democratically, despite Bosnian Serb leaders warning that “leaving Yugoslavia will drag Bosnia to Hell.” Such threats weren’t baseless. In 1992, a Bosniak shot and killed the father of the groom at a Serbian wedding in the capital Sarajevo. The next day the Serbs, fearing similar violence took action and set up fortified positions in and around the capital. Croatian, Serb and Bosniak militias took up arms and took portions of the city for themselves. Negotiations stopped the violence temporarily, but then a Serbian-Croatian deal which was made before the War of Croatian independence to carve up Bosnia based on their respective minorities was revealed to the Bosnians. The motion was to be carried through and the Serbs and Croatians surprisingly cooperated early on. This was bad news for the Bosniaks, who had to face a war on multiple fronts from outside and inside the country. In April, “volunteer” forces, which were just Serbian and Croatian armies led by local nationalist leaders, invaded. Almost immediately, Bosniaks in the lands to be given to Serbia and Croatia were arrested, and many executed. Mostly civilians. In Sarajevo, where the Serbs, Bosniaks and Croatians had lived peacefully for centuries, now demanded peace and that the Bosniak and Serbian nationalist leaders be removed from office. There was a popular peaceful march into the city center, and when it moved near the nationalist Serb headquarters, the guards fired upon the crowd killing 6 people. The government managed to capture the headquarters, but the Serbian nationalist leader escaped the city. Peace would not come anytime soon.

Serbian troops advanced into Bosnia and secured key border towns. Most of these border towns were of Bosniak majority, and thousands of civilians in each town were executed or placed into concentration camps. Many more were expelled from their homelands for which they live for nearly 500 years. In their “attempt to protect the Serbs,” they ended up committing a genocide on the scale which they feared they would be subjected to. There was a common slogan now among the Serb troops, “protect us from the Ustaše and Turci (Turks).” The Serbs now fully associated the Croatians with the Ustaše and the Bosniaks with the Ottoman invaders. The Serbs advanced into Sarajevo but were halted as they advanced towards the central government buildings. There, heavy street to street fighting halted armored advances. When a ceasefire and prisoner exchange was negotiated, the Bosniaks troops eager for revenge on the Serbs opened fire on the prisoners leaving towards Serbs lines. The civility that might have existed a year prior to the war between the Bosniaks and Serbs was over. The siege of Sarajevo continued after this episode, and the new nationalist Serb general made it a point to shell the Muslim majority communities into oblivion, to kill as many of them as possible. The Serb troops at this point had little regard for the life of non-Serbs in Bosnia with concentration camps fully operational. The brutality of the wars between the Serbs, Bosniaks and Croatians would seemingly divide them permanently despite how similar they really are.

The UN was forced to intervene when a UN colonel was not allowed to leave a besieged Bosniak town by its inhabitants. Led by Venezuela, the Non-Aligned block of the UN forced the UN to declare the town a safe area, which in legal terms meant nothing. It did however, force the UN to get itself involved in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1993, the UN proposed the Vance-Owen plan which would give each of the three ethnicities their own autonomous provinces in their respective majority area. All parties agreed to this at a conference in Athens. When it was the turn of Bosnian Serb forces to vote on whether or not accept the Vance-Owen plan, they produced a map showing that the Serbs would lose a lot of land which they now occupied. The Bosnian Serbs voted no to the plan and no to peace. The Bosnian Serbs now consolidated their state into the Republic of Srpska, and the Bosnian Croats their own state in the south. The Bosniaks would be left with a few small pockets around the country. The Bosnian Croats now turned on their former Bosniak allies and imprisoned thousands of them in concentration camps. The conditions were horrible, the prisoners were malnourished and kept in hot dirty conditions. The Bosniaks realized that they were fighting for their very survival, and fought to the death, halting Croatian advances. The US had been out of the conflict for the majority of the time, but in early 1994 realizing the EC was incapable of solving the crisis, intervened. Through threats of sanctions forced the Croatians and Bosniaks into peace. In exchange for giving up the Bosnian lands, the US and Bosnia would help regain the lands that were still occupied by the Serbs.

The US convinced NATO to then force the Serbs to end their 18 month siege of Sarajevo, which the Serbs complied with Russian forces entering the area. The Serbian fears of foreign intervention had been realized. They still ignored NATO threats and even took UN peacekeeping forces hostages to the embarrassment of the US. The US encouraged the Croatians to arm its military in order to retake Serbian rebel held part of Croatia. In mid 1995, the Croatian military successfully expelled both the Serbian troops and civilians, about 100,000 were forced from their centuries old homelands. Entire Serb villages were burned and many civilians brutally murdered. The Bosniaks and Croatians now cooperated and through a lightning offensive managed to retake most of western Bosnia, forcing the local Serbs out of their homes. Under increasing US pressure, the Republic of Srpska had to agree to a ceasefire. After a tense 17 day negotiation in Dayton between the Serb, Bosnian and Croatian presidents, the US under Bill Clinton forced a lasting peace in Bosnia. The country would be divided into the Muslim federated lands and the Republic of Srpska with the Croatians gaining autonomy is several areas.

The 4 year conflict had caused hundreds of thousands of deaths of Croats, Bosniaks and Serbs with each suffering ethnic cleansing. Though the peace treaty at Dayton ended the conflict, it was brutal one that instills national hatreds towards each other to this day. The relations between Serbia, Bosnia and Croatia will take decades to properly heal, as while they are of three faiths and three different identities, they still share centuries of history. Still, the genocide committed by all three sides will prevent the nationalistic tensions from subduing anytime soon. Still, the conflicts could partially be blamed on the influences of the Turks, which have their own discomforts with genocide.

Sources:

Michael Angold The Byzantine Empire 1025-1204: A Political History. New York, Longman Inc. 1984.

Sydney Nettleton Fisher and William Ochsenwald The Middle East: A History, Fourth Edition. McGraw-Hill, Inc. 1990.

Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor, trans. The Russian Primary Chronicle. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mediaeval Academy of America. 1953.

BBC, The Death of Yugoslavia, Documentary, 1995.